Prinzregentenstraße 66, 10715 Berlin

5’

5’

Following a separation from his wife Dora in 1931, Walter Banjamin left his Grunewald home to move into a private residence at Prinzregentenstraße 66, which would turn out to be his last Berlin address before exile. Initially meant to be only temporary, this new home was the place where Benjamin had, for the last time, fully unpacked his belongings including a fascinating library of some 2000 titles. Written as a sort of a dedication to his beloved literary collection, this delightful short essay explores the nature of collecting as a passion and a spiritual condition, emphasizing the mystical relationship of a genuine bibliophile to his possessions. The logic of the collection is all but rational. Determined not so much by will as by fate, Benjamin calls for a different reading of a collector’s vocation- as indicated in the piece of marginalia that he wrote in 1930: ‘Collectors may be loony – though this in the sense of the French lunatique – according to the moods of the moon’.

For what else is this collection but a disorder to which habit has accommodated itself to such an extent that it can appear as order?

I am unpacking my library. Yes, I am. The books are not yet on the shelves, not yet touched by the mild boredom of order. I cannot march up and down their ranks to pass them in review before a friendly audience. You need not fear any of that. Instead, I must ask you to join me in the disorder of crates that have been wrenched open, the air saturated with the dust of wood, the floor covered with torn paper, to join me among piles of volumes that are seeing daylight again after two years of darkness, so that you may be ready to share with me a bit of the mood—it is certainly not an elegiac mood but, rather, one of anticipation—which these books arouse in a genuine collector. For such a man is speaking to you, and on closer scrutiny he proves to be speaking only about himself. Would it not be presumptuous of me if, in order to appear convincingly objective and down-to- earth, I enumerated for you the main sections or prize pieces of a library, if I presented you with their history or even their usefulness to a writer? I, for one, have in mind something less obscure, something more palpable than that; what I am really concerned with is giving you some insight into the relationship of a book collector to his possessions, into collecting rather than a collection. If I do this by elaborating on the various ways of acquiring books, this is something entirely arbitrary. This or any other procedure is merely a dam against the spring tide of memories which surges toward any collector as he contemplates his possessions. Every passion borders on the chaotic, but the collector’s passion borders on the chaos of memories. More than that: the chance, the fate, that suffuse the past before my eyes are conspicuously present in the accustomed confusion of these books. For what else is this collection but a disorder to which habit has accommodated itself to such an extent that it can appear as order? You have all heard of people whom the loss of their books has turned into invalids, or of those who in order to acquire them became criminals. These are the very areas in which any order is a balancing act of extreme precariousness. “The only exact knowledge there is,” said Anatole France, “is the knowledge of the date of publication and the format of books.” And indeed, if there is a counterpart to the confusion of a library, it is the order of its catalogue.

Thus there is in the life of a collector a dialectical tension between the poles of disorder and order. Naturally, his existence is tied to many other things as well: to a very mysterious relationship to ownership, something about which we shall have more to say later; also, to a relationship to objects which does not emphasize their functional, utilitarian value—that is, their usefulness—but studies and loves them as the scene, the stage, of their fate. The most profound enchantment for the collector is the locking of individual items within a magic circle in which they are fixed as the final thrill, the thrill of acquisition, passes over them. Everything remembered and thought, everything conscious, becomes the pedestal, the frame, the base, the lock of his property. The period, the region, the craftsmanship, the former ownership—for a true collector the whole background of an item adds up to a magic encyclopedia whose quintessence is the fate of his object.

Walter Benjamin, Illuminations

EDITED AND WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY HANNAH ARENDT.

TRANSLATED BY HARRY ZOHN.

SCHOCKEN BOOKS New York, 1961

– – –

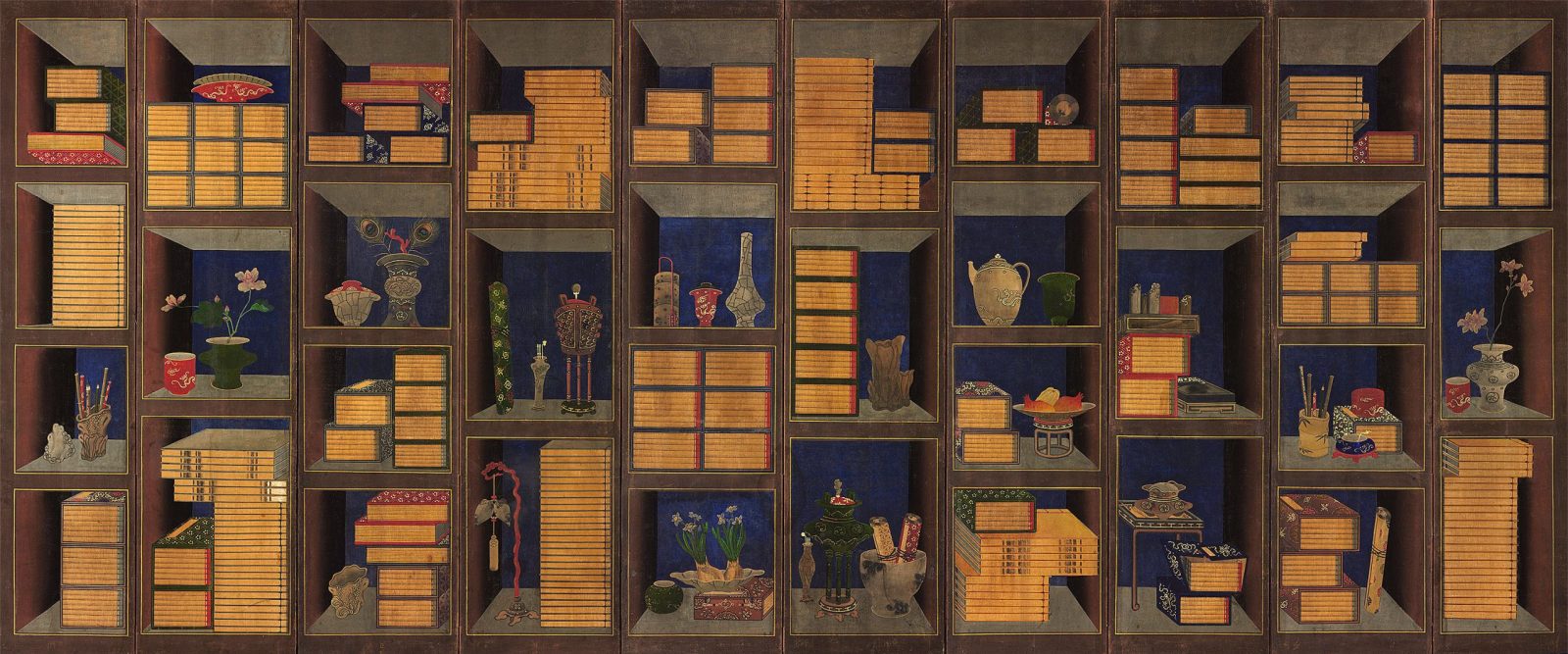

(image: Books and Scholars’ Accouterments by Yi Taek-gyun (Korean, 1808-after 1883)